Mind on

the Road

Day after day, you drive the same route to work, to school, to the grocery store. You know every detail along the way.

Those trips often become so familiar, in fact, that your mind wanders elsewhere. Instead of fixating on your lane position or checking your blind spots, you’re lamenting the 9 a.m. meeting or stressing over what’s for dinner. New technology allows a wandering mind to stray even further — to smartphones, touch screens and around-view cameras. Fueled by the advancement of self-driving cars, that’s a powerful potion for distraction.

However, NC State researcher Jing Feng is working to keep your eyes — and mind — on the road. A psychologist who specializes in human attention, Feng studies issues such as mind wandering and other behavioral and cognitive changes that occur while driving. Her research answers fundamental questions about driving habits that inform effective regulations and encourage safe design.

“We all think we are good drivers, and we don’t necessarily realize when we’re not paying attention to something important,” Feng says. “So it’s critical we study these phenomena from a cognitive perspective, to understand our limitations.”

Feng’s focus on the “how” and “why” of driving behavior helps get to the root of dire issues such as texting while driving. By identifying the reasons people look at their phones — what she calls the “underlying mechanisms” — Feng and other cognitive psychologists can inform the policymakers who create texting laws, in addition to the engineers who design anti-distraction features.

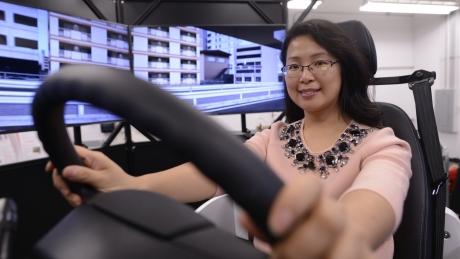

Psychologist Jing Feng discusses her research on driver attention and how she uses driving simulators in her studies. Feng's work produces new knowledge and recommendations that better inform policymakers, designers and engineers.

Feng’s work can also be applied to emerging technologies such as autonomous vehicles (self-driving cars). For example, one of her recent studies examined how drivers of different age groups respond when operating semi-autonomous vehicles. The research, which Feng conducted with NC State doctoral student Hallie Clark, found that older adults take control of self-driving cars just as quickly as younger adults. In addition, younger drivers tended to use electronic devices during automated driving, while older drivers mostly engaged in conversation, according to the study.

Working together as a multidisciplinary group, we are able to target some of the grander challenges.

To test driver behavior under realistic conditions, Feng and her research partners often use driving simulators in their research. Replicating many elements of the authentic driving experience, the simulators allow researchers to observe test subjects in precisely controlled scenarios. “For example, we could have a car turn and pull in front of a driver, or have pedestrians cross in front of a vehicle several times,” Feng says.

“The simulators allow us to observe these very important safety-critical cases without putting people at risk.” Feng’s methods also include surveying drivers to study their beliefs about driving behavior and to measure physiological cues such as eye movement and message response times.

And because research on driving behavior is intricate and impacts a variety of fields, Feng’s work is often collaborative. She routinely partners with NC State engineers, statisticians and scholars from other disciplines and institutions.

“Working together as a multidisciplinary group, we are able to target some of the grander challenges, which are very complex and would be almost impossible to address through a single discipline,” Feng says. “Multidisciplinary research also exposes the researchers to methods, views and perspectives outside of their traditional area.”

Two ongoing interdisciplinary projects (described below) provide more insight into Feng’s work.

Message Delivery in Manual and Automated Driving

As self-driving cars become more prominent, future drivers likely won’t pay as much attention to the road. Feng and other NC State researchers are studying how those attention changes will affect how drivers interact with road objects, particularly signage.

Supported by a grant from the N.C. Department of Transportation, Feng is working with NC State’s David Kaber (Industrial and Systems Engineering) and Christopher Cunningham (Institute for Transportation Research and Education) to examine the best ways to deliver important signage information to future drivers.

“We want to look at this new vehicle technology and figure out if people are still going to read road signs,” Feng says. “And if we start delivering these messages in cars, for example on an in-vehicle display, how are drivers going to take these messages and interact with them?”

Using NC State’s new state-of-the-art driving simulator, the researchers will test how subjects respond to different kinds of in-vehicle messages during manual and fully-automated driving. They ultimately hope to develop preliminary guidelines on how to deliver signage information considering new vehicle technology.

“For example, if messages are sent to cars, we need to know what the rate of communication should be, and how much information should be provided,” Feng says.

Pinpointing the Needs of Older Drivers

Another of Feng’s projects aims to help older drivers understand what cognitive changes come with age. Funded by the N.C. Governor’s Highway Safety Program, Feng is partnering with the UNC Highway Safety Research Institute to:

- Conduct a comprehensive analysis of crash data involving older drivers in the past five years.

- Survey more than 350 older drivers about their driving behaviors.

- Develop a self-assessment tool that informs drivers about how their cognitive abilities are changing.

Feng says the end result could include cognitive training and rehabilitation methods for older drivers. That could mean pointing out typical driving situations that pose more risk to an individual experiencing cognitive decline, such as making left turns.

“We want to find ways to assess an individual’s cognitive changes and provide training or advice that is tailored to those individual needs,” Feng says. “Everybody’s different.”

For more information on Feng’s research and the NC State Applied Cognitive Psychology Lab, click here.

CATEGORIES: Fall 2017, Psychology, Research