Elections 2020Experts Answer YourQuestions Before Election Day

During this truly unique election season, we asked some of our faculty experts to share their perspectives on issues — from the pandemic to politics, religious leanings and social media — that influence our voting decisions.

How do major events like a pandemic impact elections?

It is challenging to generalize about the impact of pandemics on elections. Fortunately, we have so few instances for comparison.

One event, however, does give us material for thinking about governance during disaster. The midterm election of 1918 occurred amidst the “Spanish Flu” outbreak, the largest pandemic in modern history. The first wave of influenza started in March, and then erupted across the nation in early fall — just as candidates would have ramped up their campaign appearances.

With little legal standing and no tradition of action at the federal level, other than public health advice, state and local officials decided how to respond. Infection rates varied widely among states and cities, making it difficult to invoke nationwide measures. Attempts to rapidly produce a vaccine led to the release of some with promise, but which sadly failed to work.

Infection rates and numbers of deaths were frightful. Public health officials drew on traditional measures of quarantine and what we now call social distancing. Governments closed businesses and public facilities, debates raged about opening or closing schools, and Americans took to wearing mandated masks in public.

Did it affect the election? Legal scholar Jason Marisom points to the 10% lower turnout compared to the midterms of 1914. At the least, hundreds of thousands of potential voters were ill. Then again, the press encouraged voting as a patriotic wartime act. There was little discussion of postponing the election, or doubting the legitimacy of the results. The public perhaps considered that disease did not discriminate between parties.

For us, the unanswered question is how health disparities within communities, then and now, affect voting.

Historian Will Kimler studies the history of evolutionary ideas. He is associate head of the Department of History and directs the Jefferson Scholars, a dual degree program between our college and the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Will interest among young people in the Black Lives Matter movement translate to votes on Election Day?

This upcoming election is one of the most pivotal of our time. Amid the Black Lives Matter movement, COVID-19, and the everyday issues that are important to each of us, we must elect a president.

Young people (ages 18-24) will be an important voice in deciding the winner of the 2020 presidential election. According to the Center for Information and Research on Civic Learning and Engagement (CIRCLE), young people are even more politically engaged than during both the 2016 and 2018 election cycles.

More than a quarter of young people say they have attended a march or demonstration. This is more than four times the participation from the 2016 election cycle. Even more, more than 80% of young people believe they have the power to change the country. Young people are participating in social and political change now more than ever, and they believe they can make a difference.

What are the top issues that young people care about? According to CIRCLE, young people care most about the environment, racism and affordable healthcare. These are just some of the issues that motivate participation in politics, from the voting booth to the protests in the streets.

So, will interest in the Black Lives Matter movement translate to Election Day for young people? Absolutely.

Psychologist Elan Hope researches Black youth and activism, civic engagement, academic achievement and racial identity. She says the fundamental question driving her research is what makes racially marginalized adolescents and emerging adults successful and well-functioning members of society. She runs the Hope Lab in NC State’s Department of Psychology.

What factors affect someone’s political leanings?

To paraphrase Lady Gaga — they were born that way. At least to some degree. There’s some pretty compelling political science research — based on studies of twins — that suggests that a person’s political beliefs can be about 50% explained by genetics.

The environment one grows up in is also very important. Parents and family members directly impart political beliefs and a political environment. Of course, it doesn’t always stick, but there’s a big difference being raised in a white, rural home with Fox News on TV all the time versus a multi-cultural, diverse urban environment with MSNBC.

Our demographics (race, education, income, geography, religion, etc.) are not determinative, but they do place us in particular social environments that tend to reinforce either liberal or conservative viewpoints.

Most Americans come to a fairly stable political identity by early adulthood that tends to only strengthen over time. But major disruptions to the political environment (e.g., a recession, a figure like Donald Trump) can bring about change and major disruptions to the personal environment (e.g., marriage, social status, geography/neighborhood) that can likewise bring about change.

Political scientist Steven Greene studies psychological approaches to voting behavior, partisanship and public opinion. He’s regularly called upon to share his expertise related to national and North Carolina politics, including parenthood and politics, and gender gaps in political attitudes. Greene is on the political science faculty of NC State’s School of Public and International Affairs.

How do political conversations on social media affect someone’s personal beliefs?

The research on socio-political posts on social media consistently finds evidence for increased polarization of views among social media users.

While the internet provides the potential for users to be more aware of diverse views, people tend to search for information that validates existing beliefs, which creates “echo chambers” (users hear their own voice amplified). Further, algorithms used by social media platforms curate information for users based on search histories. These two dynamics lead to the phenomenon of “filter bubbles,” where users only see views and values that reinforce their existing beliefs.

Of greater concern is affective polarization, a phenomenon in which users identify more closely with those who think like them and further differentiate themselves from the “other,” reinforcing an “us versus them” mentality. Studies have found that Facebook users, for example, are more likely to unfriend/unfollow someone who posts a contradictory viewpoint than to engage in direct exchange of ideas or dialogue.

There is one subtle way users might have influence on social media. Dolly Chugh (New York University School of Business) observes that there will always be people on opposing sides of any issue — or political post, in this context. But there’s another group: people observing those posts who are undecided and may be influenced by their perception of the majority opinion.

By communicating our agreement or disagreement with a social media post (without picking a fight with the author, whose mind is already made up), we may send an important signal that has some influence on those who are undecided.

Jessica Jameson’s interdisciplinary research encompasses organizational communication and conflict management. She also studies the power social media can have either to build up communities or dehumanize whole groups. Jameson is head of NC State’s Department of Communication.

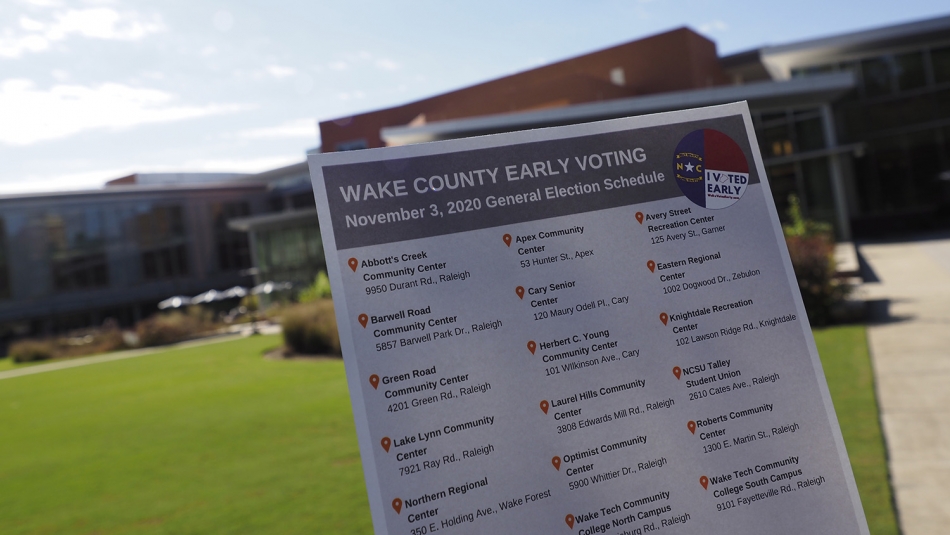

What will influence how North Carolina votes for president?

Like citizens across the country, North Carolinians are paying attention to the big issues of the year: the coronavirus crisis and social unrest surrounding issues of policing and racial equality.

Views on management of the pandemic should hurt Trump, although with a Democratic governor leading the response in our state, matters of accountability are somewhat blurred. Responses to the other events of the summer are conditioned by party. Democrats see them as peaceful efforts to promote racial justice, while Republicans see them as threats — often violent ones — to property and the rule of law.

It is interesting how the economy has been relegated to a minor role. Much of this is a function of party, with Republicans seeing it as a “glass half full” to justify support for Trump, and Democrats being more pessimistic. But I also think this is due to a realization that the current situation is temporary, and the future incredibly uncertain.

North Carolina is a swing state in all of this. We are increasingly purple at the presidential level, with the GOP generally a slight favorite — Trump won here by 175,000 votes in 2016. Barack Obama was the only Democrat to win the state since 1976 when he was first elected in 2008, and just by 14,000 votes.

As a result, the candidates will battle intensely for the state’s important 15 electoral votes. Trump and his surrogates have already been here a great deal. I think their campaign realizes there are many more likely scenarios where Biden loses the state but captures the White House than those with Trump defeated here but victorious overall.

Andrew Taylor is a professor of political science in NC State’s School of Public and International Affairs. With extensive expertise in American politics and policy, he is called upon regularly by local and national outlets to discuss the U.S. Congress, North Carolina politics, campaign finance and public policy.

How does our religious orientation impact political decision-making?

Despite the ubiquity of religion in American politics, Americans usually talk about religion using banalities. It’s obvious that religion influences policy positions, party affiliation and activism. It’s also obvious that religion is far more complex than simply church attendance or theology.

But in order to understand how religion influences polarizing conversations about health care, racial justice, or conspiracy theory, it’s important to look at religion’s relational and informational orientations. What kinds of relations do I mean? Religion is not constituted only by social networks or institutional affiliation, but also by how those affiliations do or don’t encourage openness to the experiences of other people’s suffering.

This isn’t simply a factor in the social justice movements of 2020, but a through-line connecting the religious intolerance of the Puritan commonwealths, 19th-century Nativists, and contemporary white nationalism. A different relationality is found in a history that reads the First Amendment expansively, which rejects nativism for religious cosmopolitanism, and champions religious diversity as America’s greatest strength.

Those perspectives often depend on the informational orientations religions promote. How does a particular religion construe external authority or expertise? What kinds of information do religious people consider valid: a Q-Anon tweet or a bipartisan intelligence report? It also determines whether, for example, religions will concede that an immunologist is more reputable than a lay pastor. In other words, a practitioner more likely to accept that religions have a limited sphere of authority will often make very different political decisions than those who regard their authority as unbounded.

Jason Bivins is a specialist in religion and American culture, focusing particularly on the intersection between religions and politics since 1900. He is director of religious studies in NC State’s Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies.