North Carolina andthe Green Book

Editor’s Note: In this guest post, public history doctoral student Lisa Withers reflects on her work with the North Carolina Green Book Project, an effort to document Green Book sites across the state.

“[Did I have] a copy of the Green Book? Yes, of course I did. You couldn’t leave home without it. Wasn’t any way I was going to ride up and down America without a copy of the Green Book. The Green Book told me which hotels would be available to me, and that’s where I stayed at.”

— Dr. Dudley Flood, Raleigh community member

Jim Crow laws and the social customs that were used to facilitate racial segregation in the late 19th and 20th centuries varied across the southern United States.

In the North, Midwest and West regions, African Americans faced the dangers of sundown towns, locations where African Americans were not allowed after dark. One wrong move in an unfamiliar place anywhere in the U.S. could lead to embarrassment or even put an African American traveler’s life in danger.

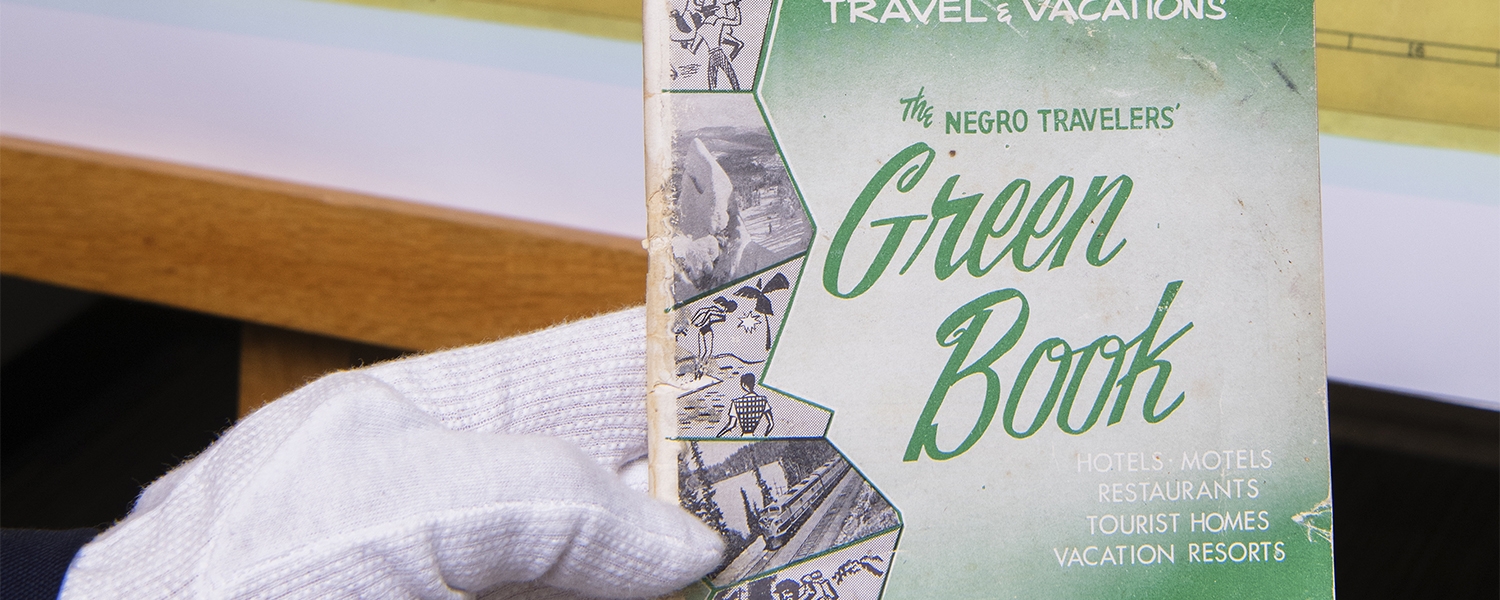

Victor Green, a Harlem postal worker, began publishing The Negro Motorist Green Book in 1936 to assist African American travelers navigating across America. As stated by Dr. Dudley Flood in the quote above, the travel guide assisted African American motorists by listing places where a person could safely get gas, food, lodgings or other accommodations.

During its 30 years of publication, the Green Book included 326 different businesses in North Carolina. The majority of businesses were located in the state’s more populated urban centers: Charlotte had 53 locations, Wilmington had 50, and Raleigh had 38. While a portion of Green Book sites were also located in the state’s rural areas, not every county was represented in the travel guide.

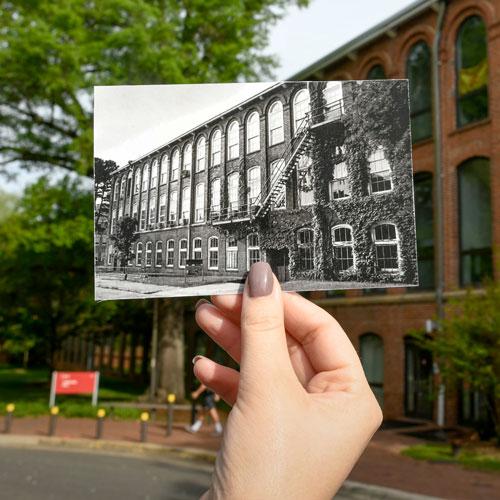

The NC Green Book Project aims to document the hundreds of locations listed in the Green Book across the state. The project team, which I’m happy to serve on, is verifying how many physical structures have been demolished or are still standing; gathering archival images; and taking modern-day photographs of Green Book locations.

Public history doctoral student Lisa Withers discusses her role as research historian for the North Carolina Green Book Project. She's joined by Raleigh resident and Green Book Project participant Sylvia West, who shares stories from her childhood and speaks to the importance of the statewide initiative.

We’re also collecting community stories about Green Book sites and the experiences of African American travelers such as Dr. Flood throughout the state. This information will be available through a web portal, two identical traveling exhibits, and a series of public programs starting in March 2020.

I serve as the research historian for the NC Green Book Project, which complements my doctoral studies in history at NC State and provides an opportunity to combine community participation and archival research. Working in partnership with local residents to document the memories of North Carolina Green Book sites and affiliated individuals further opens the door to understanding how travel guides are records of African American histories.

One Traveler's Story

TranscriptIn working together, this project presents opportunities for preservation within African American communities, both for the remaining physical structures and community members’ remembrances and narratives of the nation’s past.

The NC Green Book Project is an endeavor of the North Carolina African American Heritage Commission, a division of the North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources, with funding from the Institute of Museum and Library Services.

Photo Caption: The top image features a copy of the 1959 edition of the Green Book, currently on loan to the NC Green Book Project. The book is on display in the lobby of the North Carolina Museum of History and will be included in one of the project’s two traveling exhibits. Photo credit: Linda Fox/North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources.

CATEGORIES: Engagement, Spring 2019, Students