Hidden in the Text

NC State English professor Tim Stinson is working with scientists to extract biological clues embedded in old books.

Teaming up with bioarchaeologists, Stinson has collected structural proteins and DNA from the pages of medieval manuscripts. Tests of the samples reveal what animal skins bookmakers used to furnish parchment, the primary material used for writing in the Middle Ages. They also provide insight into ancient manufacturing practices, economic models, animal husbandry and more, Stinson says.

“Potentially written in the genetic record is evidence of selective breeding or clues to how events like plagues affected livestock and impacted the availability, the price, or the desirability of parchment,” Stinson says. “These tests might allow me to answer questions from my own area of specialization, such as when and where these texts were produced, whereas scientists and archaeologists might be able to answer questions related to animal husbandry or the manufacture of parchment.

“It’s also this truly interdisciplinary nexus. Just as it was when these books were made, where you have scholars, you have religious writers, you have folks raising the animals, you have folks selling the parchment, preparing it, all these things, so it is today, a sort of nexus of interdisciplinary inquiry.”

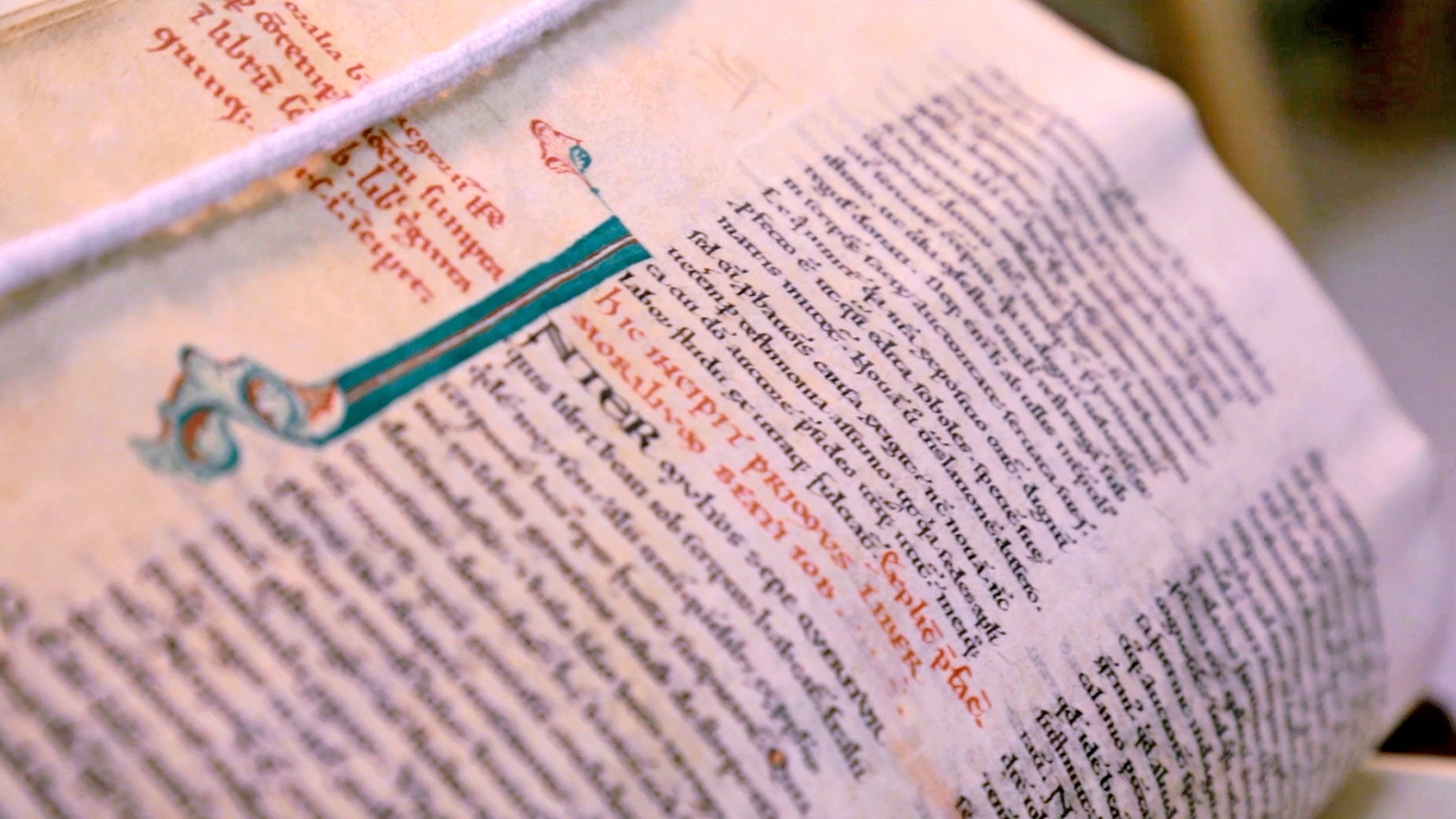

In his most recent project, Stinson tested a 12th-century English copy of Moralia Gregorii from Duke University Libraries. To obtain samples from the book, Stinson followed a testing procedure developed by Sarah Fiddyment, a scientist at the University of York in England who works in a lab headed by renowned bioarchaeologist Michael Collins.

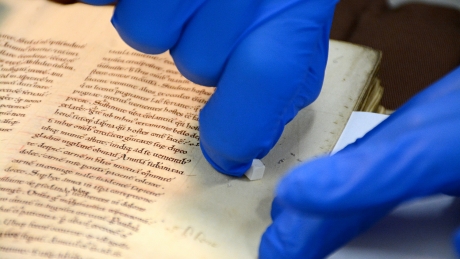

It starts with gently rubbing a small plastic eraser on the parchment pages. The friction generates an electrostatic charge that drags loose strands of collagen, the main structural protein in skin, from the material. These strands get wrapped up in small eraser fragments, which Stinson collects and sends to Fiddyment and her team for analysis.

“This process has the advantage of not damaging the parchment and doesn’t leave any marks at all,” Stinson says.

Test results show that the Duke manuscript was made mostly of sheepskin and possibly some goat, which Stinson says adds additional context for the practice of creating manuscripts. However, beyond the findings for this individual book, the test provides more evidence that this new technique actually works.

“This is only the second time ever that a complete book has been tested like this,” Stinson says. “So we’re getting proof of concept and also adding a new method to the toolbox when you have a research question.”

Stinson and Collins hope to share their work with other scholars at an upcoming biocodicology workshop they’re organizing at the Folger Shakespeare Library in Washington, D.C.

Note: The research project featured in the video above is a collaboration between NC State, Duke University and the University of York, England. Special thanks to Duke University Libraries and the Verne and Tanya Roberts Conservation Lab, where portions of this video were filmed. Testing techniques featured in the film were developed by Sarah Fiddyment at the University of York, and analysis was conducted in collaboration with Fiddyment and Michael Collins. Additional images courtesy of the British Library. Music courtesy of Free Music Archive and used in accordance with Creative Commons License.