Technology in the

Human Context

Most people are puzzled when I tell them I majored in philosophy.

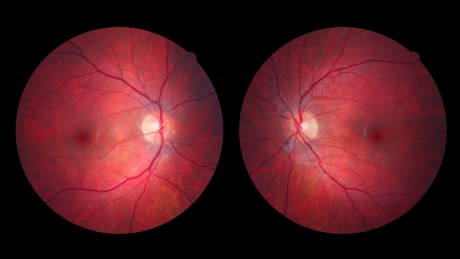

As a software engineer for Unified Imaging, a software startup based in Apex, North Carolina, I design systems for capturing, storing, analyzing and displaying ophthalmic instrument data such as retinal photos. We’ve built a platform for managing collaboration between eye care professionals so they can focus more on providing health care than running a business.

So when people learn about my career, they often ask, “What does philosophy have to do with software or ophthalmology?” Two answers come to mind.

First, philosophy taught me how to think critically and draw connections between ideas. These skills have been more valuable in my work than knowing a particular set of facts about computers or eye care. My job is to break down simple ideas into the complex details needed to implement them, while also communicating these details in a simple way without losing sight of the big picture. For example, the user interfaces we design for doctors need to be simple, even though the background processes that handle their data are complex. Achieving this balance has been more important than anything else I do in my work, especially at a small company with limited resources.

Second, NC State’s Cognitive Science Program, housed within the Department of Philosophy and Religious Studies, taught me to take an interdisciplinary approach to solving problems. Cognitive science studies the mind by connecting different perspectives in psychology, philosophy, neuroscience, linguistics, anthropology and computer science. Each discipline offers different kinds of answers to the same questions, such as “What is language?” The challenge is to connect these answers for a more complete understanding.

At the intersection of health care and technology, the situation is similar. We have to consider a patient as a person, a customer, a user, and yet we also have to represent that person as data. Here too, an interdisciplinary perspective becomes essential in order to relate ideas between clinical, business and software contexts.

With enough motivation, you can do anything. The trick is knowing what matters.

Although my role at Unified Imaging is mostly technical, the innovation we strive for cannot be achieved through technical means alone. Knowing how to create something isn’t enough without also knowing what to create and why. The key is understanding what matters for the human experience. I came to appreciate this by comparing perspectives in the humanities and the sciences through studying philosophy and cognitive science.

As my work progresses into using data for artificial intelligence, I’ve gained a deeper appreciation for knowing what matters. Our ability to understand context and relevance is precisely what makes the human mind unique. This capacity matters more now than ever, as we are increasingly inundated with information. Just as experimental data in the sciences is only meaningful when interpreted in the context of a theory, big data in our lives is only useful when it can be analyzed and put to use toward the right goals.

While in school I was often asked, “What can you do with a degree in philosophy?” My answer now is simple. With enough motivation, you can do anything. The trick is knowing what matters.

Tim Prudhomme is one of more than 38,000 Humanities and Social Sciences alumni thinking and doing around the world. Tell us how you’re using your degree.

CATEGORIES: Alumni, Philosophy, Spring 2017